At an altitude of 1,300 m, the village of Saimbeyli[1] (Armenian: Hacen) straddles the strategic road that links Feke to Kayseri and the Cappadocian plain.[2] Saimbeyli is built along the slopes of two adjoining valleys (pl. 185b). A natural spur of rock provides a majestic foundation for the fort which is located at the extreme southern end of the outcrop (pl. 185a). This V-shaped spur is at the junction of two major tributaries. The Obruk Çay, which cuts the route for the north-south road, is on the west flank of the fort. Today most of the modern village of Saimbeylioverlooks the Obruk Çay. From the east the Kirkot Çay flows through a steep valley and merges with the Obruk Çay directly south of the fortified outcrop (pl. 185b). Before 1920 the valley of the Kirkot Çay held a substantial portion of the Armenian settlement.[3]

Although Saimbeyli (Hacen) is mentioned frequently in studies on Armenian Cilicia and is the subject of an 857-page monograph, we have no documented information on the foundation of the medieval fort or the nearby monastery of St. James.[4] Because of its isolation, Hacen did not play a prominent role in the politics of the Armenian kingdom. The fortification and garrison were placed here because of the proximity to a major road. After the fall of the Armenian kingdom, the importance and size of Hacen increased dramatically. In the second half of the nineteenth century the Armenian population numbered over twelve thousand.[5] Aside from the monastery of St. James, which is at the far northwest end of Saimbeyli, fragments of the Armenian settlement can be seen in the Kirkot valley and along the top of the outcrop.

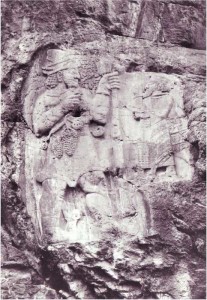

There is a relatively easy approach to the fort at the southwest end of the outcrop (pl. 185a). The trail zigzags past the south wall of a two-story brick and concrete structure, which was dedicated in 1912, and turns to the north. Because the height of the natural cliff diminishes at the northwest end of the fort, the medieval masons scarped a vertical face to continue the rock barrier and limit the line of access. The modern trail follows the base of the cliff and abruptly ascends to the terrace northwest of towers A and B (fig. 62; pl. 186a).

The masonry of Saimbeyli Kalesi is entirely in keeping with the architectural traditions of Armenian Cilicia. The vast majority of the exterior facing stones consist of type VII masonry. In some cases the consistently rusticated face of type V is evident. It is also quite interesting that in some of the courses the margins of the type VII have been stuccoed with white mortar and studded with small dark stones. Such a technique normally occurs with the poorer quality rusticated stones of type VI masonry, where its wider margins give the exterior stucco a firm anchorage. The attempt to stucco the relatively thin margins of the type VII may have been done for aesthetic effect. On the interior of the fort there are a number of types of facing stones. At the extreme south in salient E type III facing stone is common; it occurs again along the west wall of F. Type IV is also present in room D (pl. 186b). In the wall north of chapel C the interior facing improves decidedly, for in this area types V and VII seem to predominate. This is also true for the lower half of the north circuit (flanking A and B). But the upper half was refaced at a much later date (fifteenth century?)[6] This post-medieval masonry (pl. 188a) consists of recycled blocks and fieldstones bound in a thick matrix of mortar and covered with plaster. This crude masonry is also anchored by horizontal wooden headers in the core (pl. 188b). The square area marked as H on my plan stands today only to its foundation. What survives is an extremely crude masonry of fieldstones bound in irregular courses by rock chips and small traces of mortar. The walls of H, which probably are the foundation of a post-medieval church, have a poured core.

This fort consists of a high fortified circuit wall that cuts off and surrounds the tapering end of the spur (fig. 72). There is no evidence of outworks or ditches preceding the north wall. This wall runs from one side of the cliff to the other. This barrier was joined at the east (pl. 187a) by a wall of equal height that extended from the tower-chapel C. The upper portion of this east wall has now collapsed. On the other side it appears that the original west wall, which connected with tower G, was only about 60 percent of the height of the north wall. At the northwest junction the upper section has been squared off, clearly showing the reduced height of the west wall (pl. 188a). The west wall, like the one at the east, rises directly from the cliffs.

The north wall was opened by a single gate in the center that was flanked by two horseshoe-shaped towers (pl. 186a). Today, in the area where the gate once stood, there is merely a large hole in the circuit. In the lower level of tower A (not shown on the plan) the wall is well preserved on the exterior, except for a puncture at the east. Only a section of the upper level of tower B still has facing stones in site. Each tower has a single apsidal chamber at the first and second levels. In the lower level tower A was probably opened by a single door at the south. It is unlikely that the breach in the tower’s east side held a postern or window. As in tower B, only the walls in the lower-level chamber of A have been stuccoed and painted (pl. 188b). The same stucco was applied to the inner face of the north wall of H. The second level of tower A is opened by two embrasured loopholes. The one at the north is undamaged and has a small stirrup base. Because of damage to the upper level of A, only the inner side of the east embrasure is visible today.

The difficulty with the upper level of A, and likewise with the same area in tower B, is to determine the means of access. In neither of the upper-level rooms is there evidence of a door at the south. In tower A only a small portion of the open south end (in the west corner) appears to have been walled. This fragment of wall, as well as the squared top of tower A, probably dates from the fifteenth century when this tower became the base of a square campanile.[7] In medieval times ramparts probably topped both of the towers. Because the inner face of the north wall of the fort is so heavily reconstructed, we can only assume that a crenellated staircase once gave access to the ramparts and second level (cf. Yilan and Tamrut). There is the possibility that wooden structures were built directly onto the interior of the north wall in medieval times. The presence of joist holes in the refaced areas indicates that wooden beams were used in the fifteenth century.

Tower B is quite similar to A at the lower level, except the former has a straight-sided window with a miniature casemate on the interior (this opening is depicted on the plan between the two upper-level embrasures). This opening could provide only a small amount of light and ventilation. Both of the embrasured loopholes in the upper level of B are damaged. At the south end of the second level the masonry in the vault consists of long crude slabs laid radially. Toward the north end of this room the apsidal ceiling is constructed with a large type V masonry. This is quite different from the masonry in the upper level of tower A (pl. 188b), where more crude stones in a thick matrix of mortar are common at the north. This difference in masonry types is certainly due to several periods of construction.

What is left of chapel C conforms to the design characteristics of Armenian ecclesiastical architecture in Cilicia (pl. 187a).[8]

South of the chapel there are two adjoining rectangular chambers. Only the foundation of room D is visible today (pl. 186b); its function unknown. Directly to the west is the vaulted cistern F. Except for a small section at the east, the vault is well preserved (pl. 187b). It is stuccoed like the interior walls and is opened by a single square hatch. The only other evidence of an opening in the cistern is a small round-headed window at the top of the west wall. Although much of the masonry of cistern F is fairly crude, the exterior of its west end is constructed with type VII masonry, since it extends into the space of what should be the circuit. At the far south, a fingerlike projection of rock is surrounded by a single wall, forming the rounded bastion E. The function of a thin ledge on the interior of the circuit is unknown. At the north end of E and just south of room D are the remains of some scarped graves (pl. 186b). These tombs probably date to the fifteenth century, when the fort was converted into a cloister. Tower G, which is badly damaged today, appears to have been a solid bastion (pl. 185a). Only a few fragments of the circuit connecting G to the north wall are visible today.

[1] The plan of this hitherto unsurveyed site was executed in July 1981. The few contour lines of the relatively flat outcrop are at intervals of 75 cm. Only the upper levels of towers A and B are represented on the plan; the rest of the fort is represented at ground level.

[2] Texier, 583 f; Hogarth and Munro, 657 ff; Hild, 127 ff, maps 11 and 14, pls. 98-99; Alishan, Sissouan, 62 ff; Schaffer, 90 f; Sterrett, 239 and map 2. Saimbeyli appears on the following maps; Central Cilicia, Cilicie, Everek, Marash. See also: Handbook, 69, 91, 343, 337-82, 703; Cuinet, 94 f; Rasid ad-Din, Die Frankengeschichte des Rasid ad-Din, intro., trans., and comm.. K. Jahn (Vienna, 1977), 44 and notes 78 and 79.

[3] Polosean, 106 f, 122 ff; Yovhannesean, 179-82; Aghassi, 97-101.

[4] Ibid.; Alishan, Sissouan, 174-77; King, 240 f; for a discussion of the monastery of St. James (S. Yakob), see Edwards, “Second Report,” 125 ff. Concerning the medieval name for this site see below, Appendix 3, note 6. Ramsay (281, 291, 312) believes it to be the late antique Badimon.

[5] The Armenian community here and in Sis occasionally prospered as a result of alliances with the local derebeys. See A. Gould, “Lords or Bandits” The Derebeys of Cilicia,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 7 (1976), 485-506; cf. A. Sanjian, The Armenian Communities in Syria under Ottoman Domination (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), 233 ff.

[6] Edwards, “Second Report,” 130: f.

[7] Ibid. The square campanile was part of the post-medieval church of the Holy Mother of God (Holy Astuacacin). Before its destruction by the Turks in 1915, it was heavily damaged on two prior occasions; first by a fire and later by an earthquake. For information on this and other Armenian churches in Saimbeyli see note 3, above; Oskean; G. Galustian, Marash (New York, 1934).

[8] Edwards, “Second Report,” 130 f.

[1] The plan of this hitherto unsurveyed site was executed in July 1981. The few contour lines of the relatively flat outcrop are at intervals of 75 cm. Only the upper levels of towers A and B are represented on the plan; the rest of the fort is represented at ground level.

[1] Texier, 583 f; Hogarth and Munro, 657 ff; Hild, 127 ff, maps 11 and 14, pls. 98-99; Alishan, Sissouan, 62 ff; Schaffer, 90 f; Sterrett, 239 and map 2. Saimbeyli appears on the following maps; Central Cilicia, Cilicie, Everek, Marash. See also: Handbook, 69, 91, 343, 337-82, 703; Cuinet, 94 f; Rasid ad-Din, Die Frankengeschichte des Rasid ad-Din, intro., trans., and comm.. K. Jahn (Vienna, 1977), 44 and notes 78 and 79.

[1] Polosean, 106 f, 122 ff; Yovhannesean, 179-82; Aghassi, 97-101.

[1] Ibid.; Alishan, Sissouan, 174-77; King, 240 f; for a discussion of the monastery of St. James (S. Yakob), see Edwards, “Second Report,” 125 ff. Concerning the medieval name for this site see below, Appendix 3, note 6. Ramsay (281, 291, 312) believes it to be the late antique Badimon.

[1] The Armenian community here and in Sis occasionally prospered as a result of alliances with the local derebeys. See A. Gould, “Lords or Bandits” The Derebeys of Cilicia,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 7 (1976), 485-506; cf. A. Sanjian, The Armenian Communities in Syria under Ottoman Domination (Cambridge, Mass., 1965), 233 ff.

[1] Edwards, “Second Report,” 130: f.

[1] Ibid. The square campanile was part of the post-medieval church of the Holy Mother of God (Holy Astuacacin). Before its destruction by the Turks in 1915, it was heavily damaged on two prior occasions; first by a fire and later by an earthquake. For information on this and other Armenian churches in Saimbeyli see note 3, above; Oskean; G. Galustian, Marash (New York, 1934).

[1] Edwards, “Second Report,” 130 f.

Resource: http://www.hadjin.com/The_Castles_of_Hadjin.htm (H.M. Keshishian)